The 2025 Nobel Prize in Medicine awarded to, Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi, for their work on “peripheral immune tolerance,”. More specifically, identifying the mechanisms preventing the immune system from attacking the body’s own tissues.

Let’s start from the beginning i.e. what is the immune system.

The immune system is our body’s defense network. Its primary role is to identify and destroy foreign microbes, such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites and abnormal body cells. The immune system is made up of the innate (non-specialized) immune system and the adaptive (specialized) immune system. B cells and T cells form the adaptive immune system and their superpower is memory i.e. once they have fought an invader, they remember it and get into action instantaneously as soon as the next time they sense their presence.

For now, let’s narrow our focus to T cells, since they are the central character in this year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine. T cells originate in the bone marrow and these progenitor cells then migrate to the thymus for a complex maturation and selection process, hence the name “T” cells. Receptors on the surface of T cells help them fight the invaders. Each receptor is unique to a specific invader and to have as comprehensive an ability to fight the millions of pathogens attacking our body, there can be 1015 receptors in each human. When harmful microbes enter the body, the immune system recognizes them as “non-self” and launches a coordinated attack to neutralize and eliminate them.

How does our immune system self-regulate i.e. does not go into overdrive attacking itself. The T cells have to undergo a test in the thymus before they are released into circulation. If they attack the body’s own proteins, these self-reactive T cells are eliminated and not released into circulation.

This year’s Nobel Prize winners identified an additional mechanism by which our immune system self regulates, peripheral immune tolerance. This was not an overnight discovery. Nothing in human biology is! Their work unfolded over several years through key discoveries:

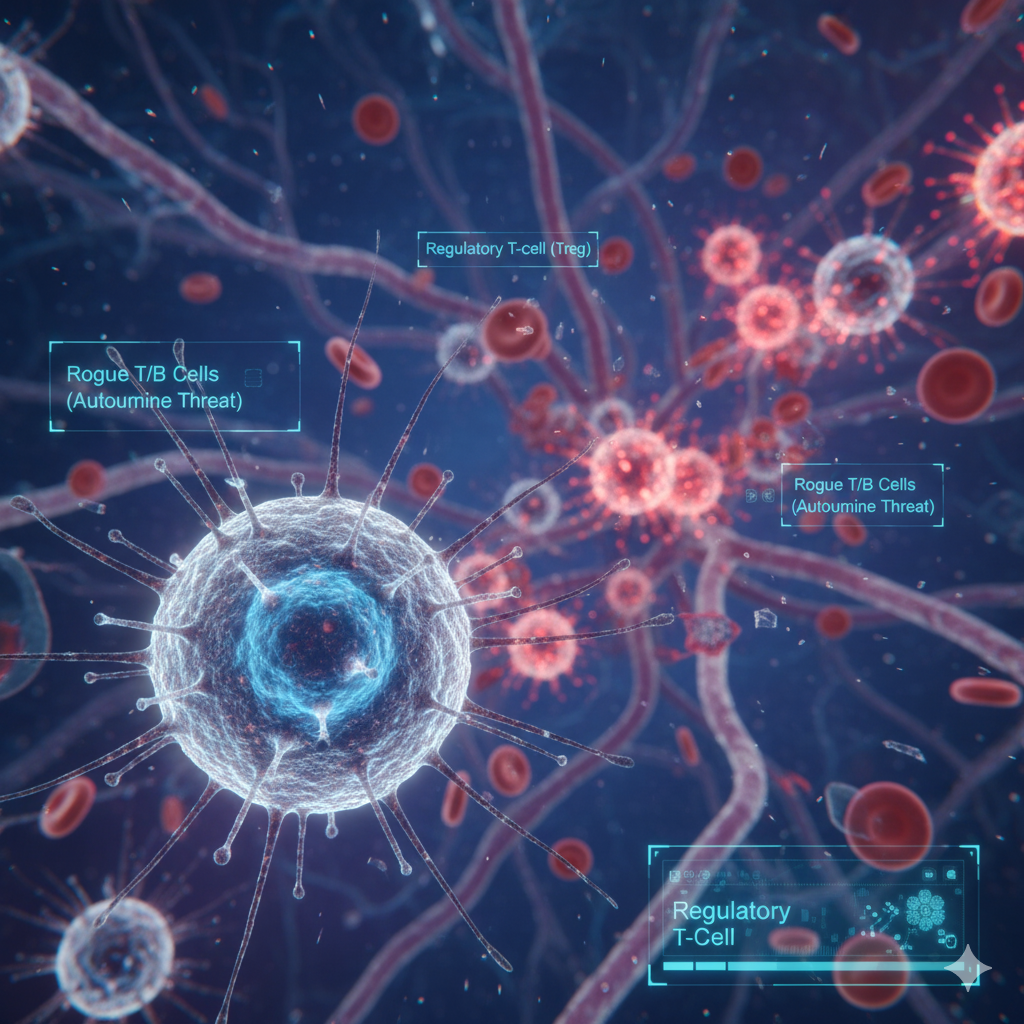

- Shimon Sakaguchi, in 1995, first identified a subset of T cells that were critical for preventing autoimmunity. He demonstrated that these cells, now known as regulatory T cells (Tregs), play a vital role in maintaining self-tolerance. Sakaguchi was the first to really pinpoint these “tolerance-inducing” T cells. He showed that these cells were vital for preventing the immune system from going rogue and causing autoimmune damage.

- Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell, in 2001, discovered the crucial gene FOXP3. They found that mutations in this gene led to a severe autoimmune disorder in mice and a similar rare condition in humans called IPEX syndrome.

- Subsequently, Sakaguchi connected these findings by proving that the FOXP3 gene is the master regulator that controls the development and function of the Tregs he had discovered earlier.

Their work deepened our understanding of immune regulation and the knowledge that dysfunctional Tregs can cause sustained inflammation and lack of homeostasis of the immune system.

Numerous neurodegenerative (multiple sclerosis, ALS), metabolic (Type 1 diabetes), and autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, psoriasis) are a result of dysfunctional Tregs and if we can boost the numbers or activity of Tregs, we can potentially calm the overactive immune system for therapeutic benefit. Organ transplants are another area where Tregs can be used to fine-tune the immune system to accept the new organ without needing massive doses of immunosuppresants. A possible future with indefinite transplant survival.

Active clinical trials using regulatory T cells (Tregs) are advancing, particularly in treating autoimmune diseases and preventing organ transplant rejection. Till date, Treg therapy has shown good tolerability but not demonstrated durable efficacy due to challenges with the small number of Tregs that can be extracted from peripheral blood coupled with low survival of the new Tregs once infused.

Efforts are currently focused on overcoming these limitations and optimizing the survival, stability and suppressive functions of Tregs. The Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maranon in Spain is trying an innovative approach of using the Thymus as a source of very high purity Tregs. They are currently running a Phase ½ trial on cell therapy with Thymus dervived Tregs to prevent rejection of heart transplants in pediatric patients. In autoimmune diseases the field is moving toward genetically engineering Tregs with chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) to improve efficacy by targeting specific antigens or tissues. This CAR directs the Treg to a specific protein on a target tissue (e.g., a protein in the joints for rheumatoid arthritis). This “GPS-enabled” Treg can then deliver potent, localized immune suppression precisely where it is needed, avoiding systemic immunosuppression.

I sign off by a quote from Dr. Claude Bernard’s, a French physiologist credited with ‘milieu interieur’ or homeostasis, “…All the vital mechanisms, however varied they may be, have only one object, that of preserving constant the conditions of life in the internal environment.”

By identifying peripheral immune tolerance, this year’s Nobel prize winners, identified the key role that regulatory T cells or Tregs play in maintaining homeostasis in the immune system and the potential for restoring immune tolerance as a therapeutic intervention in debilitating diseases.

No responses yet